Depreciating Optimism

A note on the psychology of money, time preferences, debt/liabilities, and the future

Hey reader! It’s been a busy few months. I wrote this piece as a reflection on the idea of value, rising interest rates, global money printing, and what these might mean for our future. This is NOT financial or otherwise advice of any kind, nor am I making any predictions or suggestions with this piece. I wanted to flesh out some thoughts around value, interest, debt, and how I think they relate so deeply and implicitly to human optimism.

***

In the money world, it’s all about two things: growth and assets. Assets are things you own - stocks, bonds, shares, property… some stake in some thing that holds some value, which one hopes will appreciate with some time (interest). After all, there’s a very simple philosophy behind investing — you make more money than you put in, and you don’t lose it. The investor uses their existing value (saved money) as a vehicle to generate more appreciating value (more money). Oh, and we all owe each other money.

While I’m describing the idea of monetary growth in a very obvious way here, it’s not something we think deeply about, very often. But it’s important enough to revisit, since it’s the main assumption that runs global trade and markets. This single belief that investments today will appreciate in value tomorrow, is literally the reason why the global economy exists in the first place!

Value & Debt

Money itself is often considered the purest abstraction of value, because it’s a universally accepted means of exchange. This means that money can be used to represent the value of goods and services, regardless of their inherent value or usefulness. For example, a person can exchange a piece of artwork for money, even if the person who receives the money does not have any personal use for the artwork. In this way, money acts as a neutral and objective representation of value.

When countries and banks print more money, they are essentially creating new value out of nothing. They do this by “borrowing from themselves”, to use the money to stimulate an economy (or invest in e.g., infrastructure, something expected to appreciate or add value, over the future). Thus, when we usually go in debt, it’s considered an “appreciating liability”. It’s something we owe, and as with interest and time, its value appreciates. The underlying belief or expectation as a borrower is that you are using the money (borrowed value) to invest in something (yourself, education, a house, a car) that you hope will bring some greater returns (more value) in your future. Or, you spend it on some good or service. Regardless, the value you get from using the borrowed money, should be higher than the cost of borrowing that money.

But what happens when debt, or borrowed value, becomes a “depreciating liability”? What does this mean for our belief about the future?

Interest, Time Preferences, Future Discounting

Interest refers to the amount of money that is paid or earned for the use of money over a certain period of time. This can take the form of interest paid on a loan, such as a mortgage or a credit card, or interest earned on an investment, such as a savings account or a certificate of deposit.

Time preference is a term used in economics and decision-making to describe the preference of individuals or groups to receive a benefit or reward, sooner rather than later. This preference for immediate rewards over future rewards can be seen in a variety of contexts, such as consumer spending, investment decisions, and even environmental conservation.

Interest and time preference are related in the sense that interest is often used as a measure for compensating people for lending the time value of their money. For example, when an individual takes out a loan, they are essentially borrowing money from a lender and agreeing to pay back the loan plus interest over a certain period of time. The interest is intended to compensate the lender for the opportunity cost of not having access to the money during the loan period.

One example of time preference is the concept of future discounting, which refers to the tendency of people to value future rewards at a lower rate than immediate rewards. For example, you might be willing to receive $100 today but only $80 if you have to wait a year to receive it. This reflects the idea that the value of money decreases over time, as people can earn interest or spend their money in other ways, in the meantime.

Future discounting theory suggests that people are more likely to choose immediate rewards over future rewards because they value the immediate rewards more highly. This can lead to a variety of behavioral patterns, such as a tendency to procrastinate or to prioritize short-term gains over long-term benefits. But when you borrow from banks and governments, they are also expecting a return on their investment, and that comes in the form of interest rates and more standard time preferences (like the classic 25-year mortgage structure for houses).

But something crazy has happened in the last few months - rising interest rates, happening in a recessionary climate, with high rates of inflation. This might be recipe for short-term disaster.

A Depreciating Liability

Since 2020, we’ve been facing the collective whiplash of influential governments printing trillions of dollars throughout the pandemic. By printing more money and creating “value” out of thin air, the purchasing power of each existing dollar in the market actually goes down (this is why when we print more money, inflation rates go up). Governments around the world are using different strategies to reduce costs of living. Energy costs temporarily froze, student loan interest rates reduced to zero, and the US economy entered a technical recession. But all the while, global interest rates have been rapidly rising.

In normal times, loans are usually considered liabilities. It’s a growing amount that you owe for borrowing money in the past. One common example comes in the form of student loans. In Canada, student loan interest rates have been reduced and frozen to zero (at least for the foreseeable future).

A zero interest loan is a type of loan in which the borrower does not have to pay any interest on the borrowed funds. Instead, the borrower simply repays the principal amount of the loan at the end of the loan period. In economic times of high interest and inflation rates, a zero interest loan can actually be considered a depreciating liability, instead of an appreciating liability! 🤯

Consider a student who takes out $15,000 per year for their 4-year undergraduate degree (a conservative example). Between 2016 and 2020, the student finishes their degree, graduates with their parchment mailed to their parent’s house, and leaves school with $60,000 of fresh debt. During this time period, interest rates to borrow money were relatively low, but it didn’t really matter. This is because in Canada, student loan repayment doesn’t kick in until a few months after the student graduates, and only after the graduate starts to earn money, and reaches a certain income threshold.

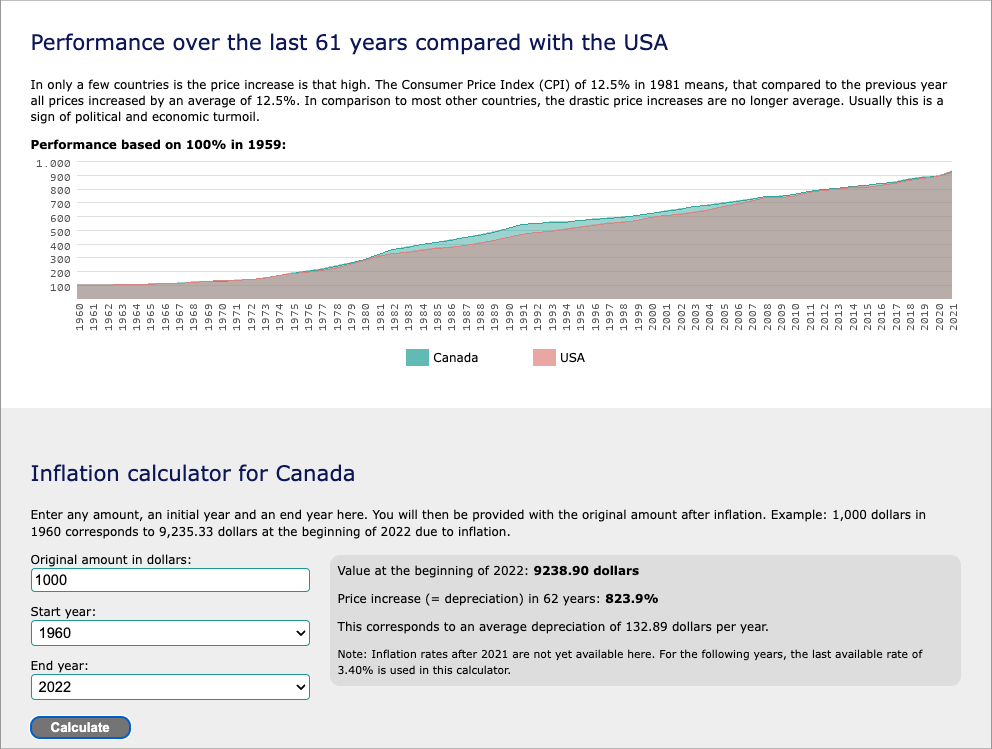

When interest rates froze on student loans in Canada, every day that the inflation rate was greater than 0.0%, the value of the $60,000 loan actually went down, not up. In fact, with inflation hovering around 6-8% in 2022 for Canada, the value of that loan is also going down by 6-8%! After all, $60k had a lot more purchasing power in the year 2000, compared to the same amount of money in the years 2010, and 2020.

Meaning, if you have any loan, mortgage, debt that you are borrowing at a rate below the inflation rate (which, at the time of writing, includes almost all types of loans, with the exclusion of typically high credit card interest rates), then your cost of borrowing the money over time has actually gone down, and not up.

If an individual borrows $100 at a zero interest rate, and agrees to repay the loan in one year. Inflation over the course of the year causes the purchasing power of the $100 to decrease. The person lending the $100 actually lost money.

In the present global economy, appreciating liabilities have become depreciating liabilities. In other words, there is a greater incentive to be in debt and pay the debt off as slowly as possible, rather than be debt free. The borrower is incentivized to not pay off the loan for as long as possible.

Time - A Liability

Time preferences and future discounting theory suggest that time itself can be viewed as a liability, because it is a scarce resource for all of us, and we don’t actually know when our time will run out. Put another way, time is our most scarce and valuable resource.

Given the limited nature of our time on this earth (death and taxes), and the general uncertainty we all have about the future, it is extremely important that we have a global economic engine that reflects some sense of human optimism about the future.

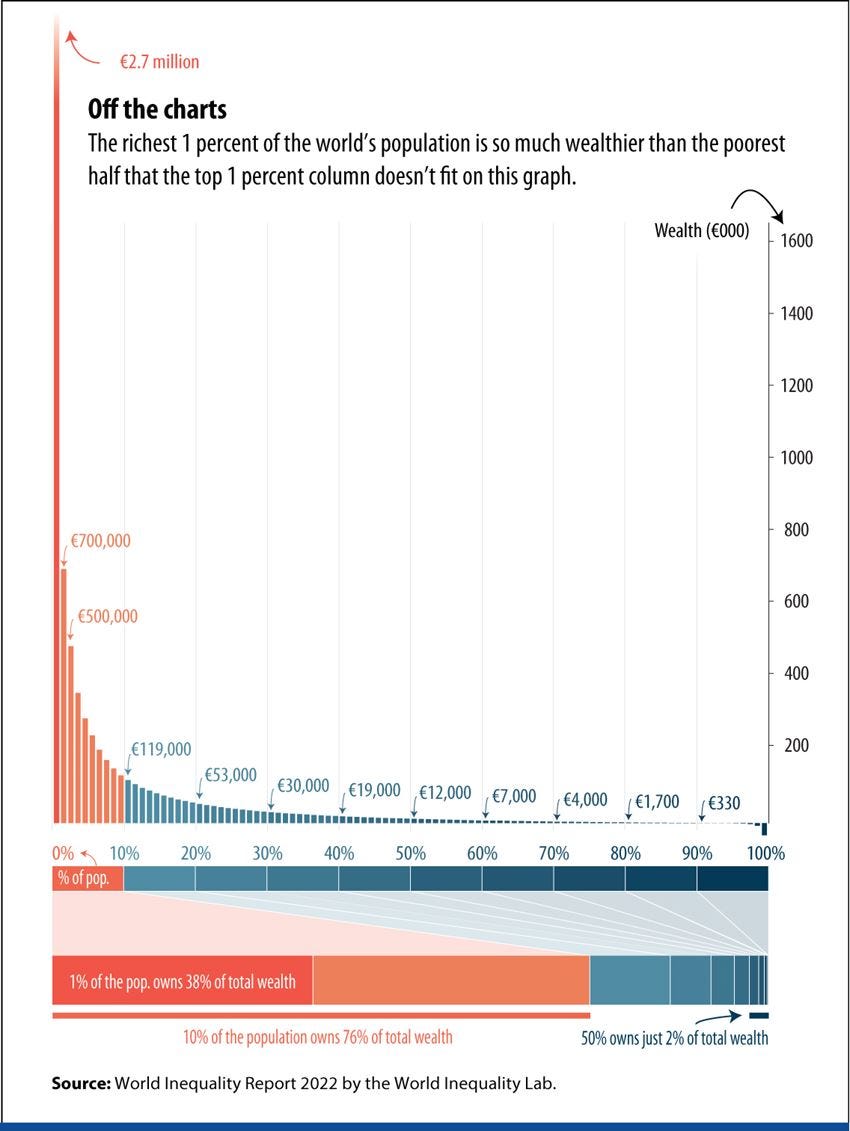

If there is an escalating battle between rising inflation rates (governments printing too much money) and rising interest rates (governments increasing the costs of borrowing money), this increasingly stressful contention ultimately affects low and middle-class workers, which make up the bulk of the global population.

I’m no economist, so I won’t argue for or against inflation (or, what is “healthy” or “unhealthy” inflation), but its important to recognize that printing more money, and increasing the cost of borrowing said money, are really the two primary tools that governments around the world have, to keep their economies going. Let’s not forget, money is essentially printed out of thin air. In essence, we are all earning, spending, growing, borrowing, and expanding entire countries from a global monetary system built on sand.

Optimism

When I put it this way, its kind of hard to be optimistic about the future, isn’t it? (sorry). When we borrow large amounts of money, often we do it to buy something meaningful to us. You might borrow to afford a future home for your family, to invest in your education, grow a business, or afford something personally meaningful, like a good (dream car), or service (traveling the world).

When we borrow value (money) from others to help us attain our goals and grow in some part our lives, the lender is generally giving you money in hopes that their investment is worth it for them. You are borrowing that money because you too have a vision for a better future for yourself, and you are borrowing money to make it happen.

When the value of the money itself is going down due to inflation, faster than the interest expected by the lender, then it spells trouble in three ways: 1) for the lender, 2) for the borrower, and 3) for the currency itself.

The lender is losing money when they are letting other people borrow it, because they are getting back in return, less money than if they had invested it in something that would grow at, or above than the rate of inflation (the lender is making a bad investment by loaning the money, meaning they would hesitate to lend more money, in the future).

The borrower might seem like they win from this deal, because they are effectively being paid to borrow the money (they will be paying back in the future, a value that is worth less than it is today, effectively borrowing for free, or getting paid to borrow!). However, the borrower also has to consider if the thing they’re buying with the borrowed money is also appreciating or depreciating in value (the future value of the home, the educational degree, the dream car). If the investment is growing slower than inflation during that time period, the borrower also loses.

Remember how I mentioned at the beginning of this article, that the money game is all about growth and assets? Whether one is in the socio-economic privileged position to lend money (typically upper class), borrow money (typically middle class), or barely scrape by (typically lower class), if you are holding assets like the currency itself ($CAD), or using that currency to buy things tied to that currency (a Canadian education, or a Canadian property), then its not just the value you are borrowing that gets affected, but the total value of everything you own in that currency is also depreciating.

I’m a determinant optimist, meaning I generally have hope that humans collectively will solve and iterate through solving hard, technical problems. But when we are living in unprecedented economic times of globally centralized supply chains, where everyone owes each other money, and where interest rates are rapidly rising, I suspect there are few escapes out of this messy situation.

Some Ways Out

While its easy to sus out big government for this (they are to blame for printing, spending, and regulating borrowing rates), its hard for any one person or group to have the knowledge to predict the future and make the best economic decisions, all of the time.

There are however, general macro trends that are outpacing inflation and rising interest rates. Meaning, opposite to depreciating liabilities, there are appreciating assets that are growing and providing increasing value to the world, at a rate that is outpacing excessive government spending and potential currency collapse. Sadly, I could only think of two clear examples (technology and energy), but you might get a sense of why, with some examples below:

Artificial intelligence systems: AI systems like DALL-E 2 (which I have outsourced to for a lot of the graphics in my articles), allow for exponentially efficient ways of creating value (new art) that would otherwise cost much more time, money, and human effort to produce.

The silicone transistor: Following Moore’s Law, consumer computer chips are getting exponentially efficient and powerful, allowing for more complex computational workloads at cheaper costs.

Automation and robotics: The most expensive cost for many organizations and systems to run, is human labour. I’m not pro-replacing all of our jobs with robots or anything, but having automated systems in place, acts as a strong deflationary pressure on the costs of goods and services for the consumer. If we aren’t getting paid more, then products need to stay affordable, and automation is one way that can happen.

Renewable energy: Breakthroughs in solar, wind, battery, and even nuclear technology, is helping us trend towards energy costs approaching zero. If we ever get to a point of unlimited, cheap/free energy, we can actually use it to create real value from nothing (without printing money out of thin area), since energy is required for every other sector and industry to run, in the modern world.

I picked these two sectors because a) the world is increasingly merging atoms and bits, and b) energy is the backbone for all other industries and sectors, and is needed for them to operate and function.

If we weren’t making progress in these two industries, as we have in the last few decades, it’s really difficult to attribute the incredible industrial growth and reduction of global poverty that we’ve seen thus far, in the 20th century. In this incredibly weird time where it can be confusing to decide wether it makes sense to lend or borrow money, the underlying assumption of future growth is intrinsically tied our optimism about the future. There is something extremely powerful behind this belief that investing in tomorrow is worthwhile, and will help us build and foster a better future than our present.

Perhaps, there is some hope that the trend-line reverses (inflation gets back in check, borrowing rates hold steady, or new monetary systems emerge). Maybe global growth stabilizes in a sustainable, optimistic, and empowering future for our collective civilization. However, we shouldn’t just assume that governments will be able to fix or solve the problem on their own, and it will take many deflationary advancements like in technology and energy, for us to get out of this mess of depreciating optimism. After all, hope in the future is intrinsically tied to human purpose. The world stops when we stop dreaming of a better future, and it would be a shame if it topples because a handful of bureaucrats couldn’t balance their budget sheet.