Solving the Principal-Agent Problem

Agency, responsibility, and incentives become elusive in more complex systems and contexts. Newer technologies like Web3 allow better incentive alignment, and might solve the classic problem

Convenience store shopping

Imagine going to a local mom-and-pop convenience store to get some snacks. The store is family-owned, has been around for a few years, and has slowly grown and gotten busier over time.

One day you walk in, and you notice there’s a new face at the front desk - the family hires someone to help run the store. When you go to pay, you notice the employee is disengaged, dressed lazily, and doesn’t make eye-contact with you. You find the interaction odd, especially as it contrasts with the great customer service you’ve received in the past, from family members running the store. There’s no small talk, no greeting, no “thanks for shopping!”, and no enthusiasm.

A couple of months later, you return to the store and find that someone else has replaced the previous employee, but again, it isn’t someone from the family. Although you interact with the new employee at checkout, the symptoms were all the same - apathy, lethargy, and a cold demeanour.

Are the family bad at hiring? Is there low morale in the work environment? Is the worker getting paid fairly? Is the job not suited for the worker(s)? Is it just a bad hiring streak? Is there something else going on here?

The Principal-Agent Problem

The principal-agent problem is a conflict in priorities between a person or group and the representative authorized to act on their behalf. An agent might act in a way that is very different, or even contrary to the best interests of the principal.

In this situation, the business owners (family members as employees) treated their customers better, were more engaging in their interaction, and had a more personal experience with their customers. For the recently-hired employee, they seemingly weren’t as engaged. Why is that?

Ultimately for the business owner, their high-level incentive is to make the most amount of money, maintain high customer retention/satisfaction, and build a reputation as a friendly, accessible, and clean convenience store. As a family business, the employees were all owners, and directly benefited from appreciation in the business value that they provided to their customers. This meant they had more skin in the game, since their stake in the business was proportionate to their reward (the family runs on the business), and not tied to an hourly wage, like the external employee.

The owners know that too low of a wage would yield lower-quality employees and disincentivize them from doing good work. If the wages are too high, the employee becomes unaffordable and the point of hiring someone to make the work easier, is altogether moot. Between the two ends of the spectrum, there is a middle-ground of price discovery, where the employer can pay a reasonable and fair wage to attract competent, long-term employees.

When hiring an outside employee, the convenience store’s incentive is to help with the management of the business, and get the most return-on-investment for their new hire, for the least amount of (reasonable) pay possible. For the employee, they are paid hourly, and so their goal is to make as much money (work as many hours) while doing the least amount of work possible. Whether the employee mops the floors, stocks the shelves, or does literally nothing, they get paid the same wage per hour, so why bother putting up with more work?

This is a fairly simplified example that illustrates the inherent conflict of interest between principals and agents. While the principal has hired the agent to scale their business and manage increased demand, the incentives for both parties are not entirely aligned. Ultimately, this creates a separation in expected value and service for the customers. The agent feels resentful towards the principal, and the principal regrets their decision to hire the agent.

You can imagine other examples where the incentives aren’t aligned between parties:

-Teacher vs. student (getting paid vs. getting good grades)

-Driver vs. passenger (travelling sober vs. travelling without worry)

-Banks vs. customers (making money vs. saving money)

-Human resources vs. employees (for the company vs. for the self)

-Divorced couple vs. their children (for the relationship vs. for the family)

-Government employee vs. citizen (minimum salary obligations vs. timely response)

-Airline vs. passenger (maximize earnings vs. maximizing comfort)

Scaled up

The previous example was a simple 1:1 comparison between one principal (family-owned business) and one agent (a singular employee working for the business). What happens when we look at this problem at a larger scale?

We’ll examine UberEats as an example of the problems of scale with the principal-agent problem. UberEats is an online food ordering business subsidiary of Uber, the company known for their famous ride-sharing app. The company has a market valuation north of $50 Billion USD, and their UberEats subsidiary pulls in ~$5+ Billion USD in revenue every year. Big bucks for a publicly listed international corporation.

When it comes to problems of scale, one of the reasons why its hard to effectively grow, is learning to manage and coordinate larger groups and sub-organizations in a cohesive manner. In more complex organizational structures, it becomes harder to discern the principal from the agent, and usually it is a complicated, multifaceted system with many moving parts.

When a customer opens the UberEats app to order late-night snacks from a restaurant or convenience store, the principal (customer) and agent (UberEats driver) are not the only principal-agents in this seemingly simple scenario.

Lets consider all potential stakeholders in this transaction, and assess who the relative principals and agents are, in each scenario:

Customer: The old adage “cash is king” rings true here… even if the UberEats order was probably paid for, using a fin-tech intermediary like ApplePay… It is ultimately the customer’s money that is paying for everything below, meaning the customer (the market economy) is a major deciding principal of agents in the market. The customer can ultimately decide to use UberEats, or any other available delivery service available in that area, at that time.

They won’t always be mentioned explicitly, but the customer is the ultimate principal for all of the scenarios below, as the customer is the one deciding to feed money and life into the business and all stakeholders.

UberEats Delivery Driver: Responsible as an agent for picking up and dropping off delivery orders for UberEats (principal) and the restaurant/store (principal).

Restaurant/Store: Responsible for packaging/sending the correct order off as an agent to the delivery driver (principal), and to UberEats (principal). These food establishments have their own inner systems with various principals and agents, as illustrated above with the convenience store example.

UberEats Customer Service: Responsible for handling any complaints from the customer (principal), when the driver (agent) or restaurant/store (agent) fail to deliver on their service and affect the reputation of UberEats (principal).

UberEats Software Developers: Responsible for ensuring the app UI/UX works on the most popular consumer (principal) smartphone devices using UberEats (principal) for all parties involved (all principals and agents).

UberEats Executive Management: Responsible as agents for ensuring Q/Q and YoY growth for parent company Uber (principal), shareholders of Uber (principal), and working towards improving customer experience (principal), in usage and features.

Uber Company/CEO: Responsible as an agent to the free market/customer (principal), shareholders (principal), board members (principals AND agents), and employees/contractors (agents).

Uber Shareholders: The principals hoping to make money on their investment in Uber (agent) the company. The shareholder has skin in the game as part owners of the company (principal), but are agents to larger free market forces. The shareholder technically owns a part of the company and stock market (principal), but their stock returns act like agents to larger market forces, at the whim of competitors, acquisitions, recessions, changes to social policy, and more.

Larger Market of Delivery Services: These are external principals that may influence the principal economic moat of Uber, the company. This includes all companies that potentially eat at Uber’s overall market share, such as local taxi chains, Lyft, SkipTheDishes, Door Dash, and Tesla (automated self-driving taxis, whenever they come).

Chain of command

»»»»»»»

Customers-Drivers-Restaurants/Stores-Employees-Executives-CEO-Shareholders-Market

You might notice that the chain of command starts with the customer, and ends with the market. This was just a brief example to illustrate some of the complexity in the game of principal-agent, in a more complex real-world scenario. Of course, the scope and complexity of principal-agents can vary depending on the type of organization, levels of management, incentive structures, and more. Important to note that in a typical large-scale organization like UberEats, the chain begins with the customer and ends with the market.

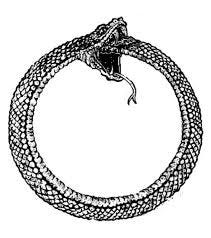

In a sense, the customer is the market, and so the beginning and end of this chain of command looks less linear, and more circular, almost like a dynamic, yet closed feedback loop.

Incentive Alignment - Present Examples

One of the classic ways in which agents in larger organizations have aligned incentives is through preferred stock options. If you are a software engineer at a technology company like Uber, your compensation is likely composed of a mix between salary and company stock. This way, the public stock price of the company (usually) directly reflects the underlying performance of the organization. If the employees perform well, the company does well, the stock prices goes up, and the employees also make more money. This aligns the incentives to be a win-win situation - the company gets more hard-working employees, and the employees make more money.

Similarly, there are other variations of this model, like co-operative businesses (co-ops), where employees have more say in the day-to-day decision-making of the organization, and they can make more money as a result of having more responsibility within the organization.

Ultimately, stock options, partial-ownership, and similar models seem to help align incentives and allow agents to act more like principals. This also leads to more principal-like thinking (how can my work help grow the business?), and less agent-like thinking (how can I make more money for doing less work?)

Incentive Alignment - The Future

The following may sound like sci-fi, but is already happening today in many variations, and the trend will likely continue in the future. The principal-agent problem naturally creates a win-lose relationship, at least in some aspects. Agents think principals are winning without sharing their earnings fairly, or principals think agents are ripping them off and getting away with doing less work. If the incentives are aligned for all members of a party to create a win-win scenario, then this will naturally be something that all participants in various parties eventually gravitate towards.

In 2009, the Bitcoin White Paper solved for the age-old problem of the Byzantine fault problem. Long-story short, this problem is a problem of social coordiation and incentive alignment, in a decentralized matter (there is no boss, no ultimate principal, and yet everyone coordinates and follows the established rules to solve the next Bitcoin block, as voluntary principals in a network with no real agents). This is a monumental breakthrough that doesn’t get enough credit for what it deserves.

Since then, the growth of Web3 has allowed for users to not only read and write data on platforms like Facebook, which own all of this data, but read, write, and own - meaning when one interacts with Web3 protocols, they also own a part of that network, and get incentivized for doing-so, using tokenomics. This means that user-aligned metrics like ownership, transparency, interactions, and click-through rates can change the way the internet works, in a way that is more win-win and less win-lose.

For example, I’m sure you’ve come across articles online that promote weight loss strategies. “Lose 5 pounds in 5 days!” or “How to have a 6 pack in 6 weeks”. These Buzzfeed-esque click-bait filled articles generally maximize for one thing: Click-through rates and retention. The publishing company makes money on your attention by promoting some weightloss product in the article, or showing banner ads on their website, surrounding their article. Regardless of whether you lose weight or not, the publisher (principal) makes money off the reader’s attention (agent). They ultimately don’t care if you lose weight, but do care that you click on their article and pay with your attention. In short: The incentives are misaligned between the writer, and the reader.

What Web3 allows is for more incentive alignment. There will one day be a method in which one can connect their crypto wallet to a blog, read an article, follow its instructions, and automatically track their weight loss over time, if the person signs up and follows the instructions outlined in the article. The author of the article makes money only if you lose weight, and gets paid out in a cryptocurrency using a smart contract that automatically pays out when users follow their steps and get results. If the article is bogus, the reader won’t lose weight, and the writer makes no money.

Suddenly, the optimizing function for the publishing company (principal) is to actually help the readers (agents) lose weight effectively, and not to simply attract their attention and make money by showering them with click-bait driven thumbnails, banner ads, pop-ups, and sponsored posts that promote some fat loss product.

Conclusion

The future of the internet is exciting. When we get to the point where Web3 protocols are adopted in the mainstream, incentives will start to align and principal-agents will look more like principals helping other principals. Cryptocurrency and automated payouts using smart contracts will enable new ways to grow audiences, make money, and actually create meaningful change and impact in people’s lives. A true win-win for the internet, the creator economy, and everyone involved in the space.

In good times, agents typically do what principals want, and principals try their best to accomodate to the wants and needs of agents. In bad times, the principal stops paying the agent fairly, or the agent doesn’t do all of the work, and starts to form resentment towards the agent.

If we were to look back at the example of the UberEats order above, you can see how something so simple can bring up complicated dynamics and incentives between different parties. In every interaction between two individuals within a larger system, there is an interplay of the principal-agent problem of alignment. Ultimately, we want more win-win pairs and less win-lose or lose-win pairwise outcomes.

The examples mentioned in this blog post have to do with economics and large organizations, but the uniqueness of the principal-agent problem is that it can be found in the smallest of pair-wise comparisons: Between couples, siblings, business partners, food delivery drivers/consumers, and pretty much anywhere you notice two or more people interacting with each other.

By recognizing the importance of the principal-agent problem and identifying congruent or discongruent incentive structures, we can optimize our lives to better orient ourselves towards win-win situations, and less towards win-lose or lose-win situations. Ultimately, playing games with win-win outcomes means that everyone is happy, everyone gets paid, and everyone is working towards the same goal. Thus, the principal-agent problem is not only bound to the realm of behavioural econonomics, but our everyday beliefs, and actions in the world.

![やれやれだぜ — xiaoxiangji: corner store aesthetics [updated] ... やれやれだぜ — xiaoxiangji: corner store aesthetics [updated] ...](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!3b_B!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0bbc463b-b19c-446b-ae37-5f1bc2b56d86_500x334.jpeg)